Bad Company’s “Feel Like Makin’ Love” is blasting inside Josh Homme’s black Escalade as he glides past a ranger’s station at Will Rogers State Historic Park in Pacific Palisades on a recent morning.

“This song is true,” Homme says, reaching for the volume knob. “But it’s not true right now.”

Homme’s dry wit and his flair for riffs have made his band, Queens of the Stone Age, one of the most widely admired in hard rock: a darkly sensual groove machine whose famous fans run the gamut from Elton John to Lady Gaga to ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons.

Formed in the mid-1990s out of the ashes of Kyuss, the pioneering stoner-metal group Homme assembled as a teenager in his native Palm Desert, Queens broke out in 2000 with “Rated R,” which opened with a chugging number called “Feel Good Hit of the Summer” whose only lyrics went, “Nicotine, Valium, Vicodin, marijuana, ecstasy and alcohol”; since then, the band has stayed busy in the studio and on the road even as Homme has pursued side projects including Eagles of Death Metal and Them Crooked Vultures (the latter a power trio with Dave Grohl of Foo Fighters and Led Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones) and produced albums by Iggy Pop and Arctic Monkeys.

“Josh has such a natural, deep-rooted feel in everything he does,” Grohl tells The Times. “He’s endlessly creative and legit funky. There’s always an element of ‘Watch this…’ that makes it so exciting when you begin a song together — like you’re playing a trick on the audience. You catch each other’s eye in the middle of a jam and just start laughing.”

Yet Queens’ latest LP reveals a different side of this 50-year-old singer and multi-instrumentalist.

Released in June, the raw and jagged “In Times New Roman …” ponders a tumultuous few years in which Homme lost a number of close friends — among them Foo Fighters’ Taylor Hawkins, Mark Lanegan of Screaming Trees and actor and bar owner Rio Hackford — and engaged in a highly contentious custody battle with his ex-wife, Distillers frontwoman Brody Dalle, whom he divorced in 2019 after a decade and a half of marriage and with whom he shares a daughter and two sons ages 7 to 17. After the album was complete, Homme was diagnosed with cancer — he won’t specify which type — from which he’s since recovered following surgery.

“When you make music, you’re putting yourself out there, and I wasn’t sure I wanted to put myself out there,” he says as we sit at a picnic table in the park, not far from his home in Malibu. He’s wearing a dark shirt, dark jeans and leopard-print Vans and offers me a tea-tree-oil-infused toothpick — a reminder of his friend Hackford, who carried a little box of them at all times, according to Homme.

“Sometimes you ask yourself, ‘Who needs my take?’ Especially if you’ve got seven or eight records, like we do. It’s a question you should ask,” he adds. “But this time it just felt like survival.”

In October, a judge granted Homme sole custody of his and Dalle’s children, bringing to an apparent end a long legal fight involving mutual accusations of physical and emotional abuse. Homme declines to discuss the ruling, explaining that, as an adult, he can’t help but to see talk of his family life on the internet. “But my littles can,” he says. “And I want them to make that choice when they’re the right age to do that.” (Dalle didn’t respond to an Instagram message seeking comment.)

Grohl, who’s known Homme for more than 30 years, says their bond “goes far beyond the music stuff. It’s life stuff. We’ve both been there for each other — moments where everything else is stripped away and all that you’re left with is real vulnerability and fragility.

“But I’ve never seen the guy give up,” Grohl adds. “He’s just not that type.”

Queens — whose other members are guitarist Troy Van Leeuwen, bassist Michael Shuman, keyboardist Dean Fertita and drummer Jon Theodore — will play its final concert of 2023 on Saturday night at the Kia Forum.

In addition to some of the band’s many friends, Homme notes with pride that his kids will be at the show. “We’ve gone through all this together,” he says. “I take them with me everywhere.”

“I like risky things. I like to throw myself off the cliff. I’m willing to do stuff you aren’t — that’s what separates us,” says Josh Homme.

(Andreas Neumann)

You were wearing a Van Dyke beard earlier this year, but now it’s gone.

It was a symbolic beard. There’s a thing about sailors: They shave the day before they leave, then they don’t again until the journey is over. I was subscribing to that notion. My old life was ending in many ways, including an illness that I probably got from the stress of it all, and until my old life was put to bed, I was like, This is me now.

What made you know your old life had ended?

My family was OK. And I was OK. I guess acceptance is what happened.

Did you like making the latest record?

I liked having made it. It’s getting harder and harder to do, because I put so much pressure on wanting to be raw, vulnerable, honest. How much more honest are you going to be? It’s more the words. I like messing with arrangements and all that stuff. But it was just hard to know what to say.

Hard to know what you felt or hard to put it into words?

Hard to put how you feel into words. It’s finding the right spot where you’re being honest and not cryptic, but you’re not being like, “Tina was supposed to babysit but she’s at her boyfriend’s house,” you know what I mean? I listen to the radio, and I’m not in love with tons of the lyrics I hear. It’s more like a journal or just a to-do list. Words should be colorful and explosive. There’s a book called “The Gruffalo.”

A kids’ book.

The iambic pentameter of “The Gruffalo” is so f— good. I mean, it’s perfect. I want some of that.

You’ve often veiled real-world situations in language from fairy tales.

The hardest thing for me to say is “I love you.” I don’t want to be in love. I don’t want to love stuff. I don’t like looking at pictures. It makes me sad — it’s everything that was and is not. Nostalgia hurts. I watch my kids sleep, and it makes me feel awful because I love them so much. I often wonder if love is a mental health issue. When you love someone who’s not your blood, you take everyone else you love and you say, “I hear what you’re saying, but I’m gonna ignore that and just believe this thing.” And I’m an idealist: I see where you and I could go together. But if you don’t have the guts to say what you mean, we’ll never get there.

That’s heavy energy to bring to a date.

This wouldn’t be the energy I would bring to a date. This would be the energy I’d bring to making a life with someone.

Is that something you’re interested in?

I don’t think I could ever do that again. I fell in love once, and I’ll always be in love with that person. Always. Forever. It’s the love of my life, and I did the very best I could. And that’s OK. I’ve got these beautiful babies, and that’s a wonderful thing.

You might live another 35 years—

There’s no f— way.

But living however long without another romantic relationship — that doesn’t feel lonely?

Certainly doesn’t now. I want to work on being a good brother. A good son. A good father.

You’re close with Dave Grohl. Did the two of you commiserate as you were going through the rough times that define each of your albums?

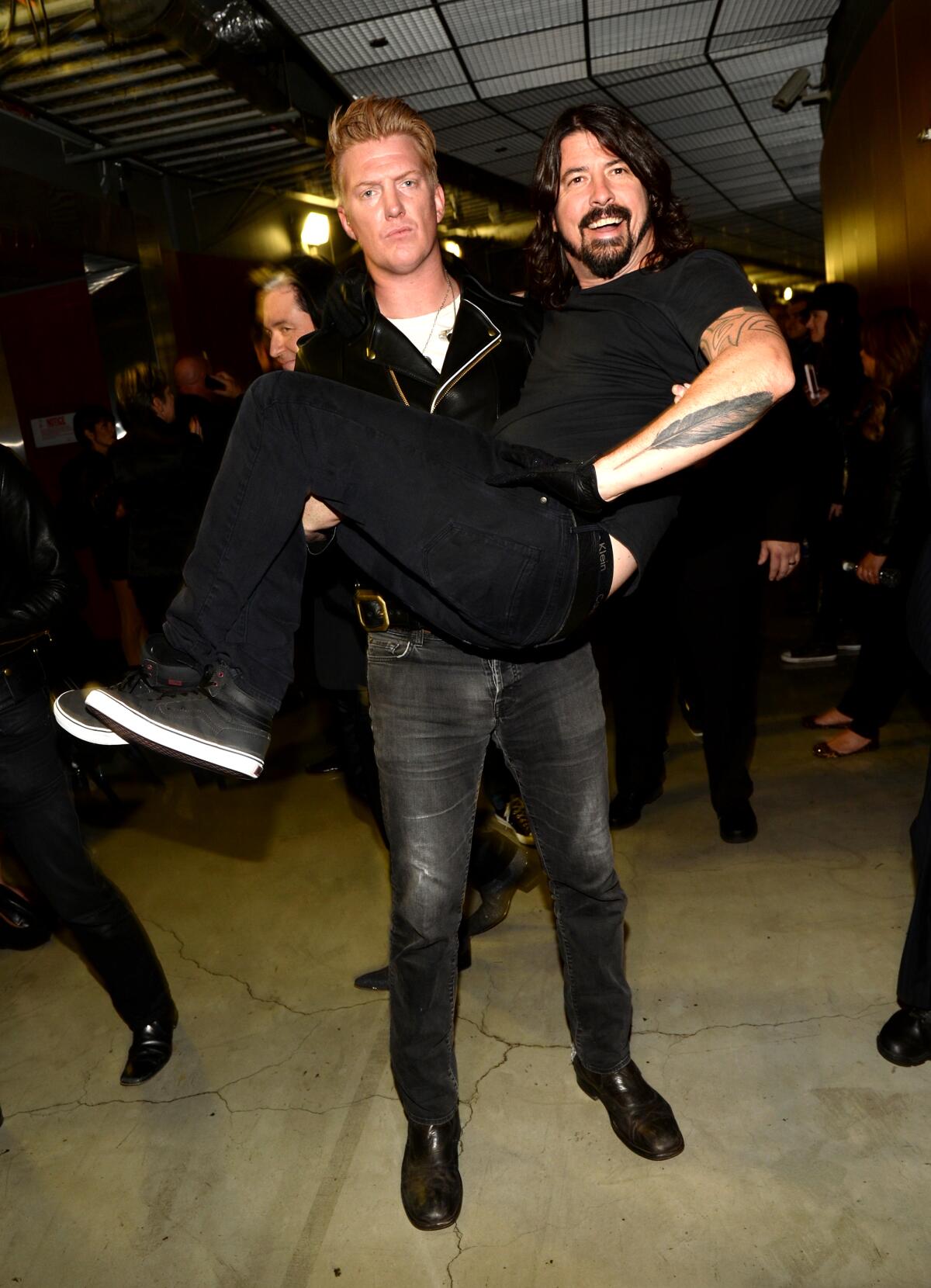

Look, Dave’s been the other love of my life. I know everyone’s like, “Dave’s your buddy!” And I agree. But it’s in our dark moments that he and I have gotten close. You don’t have a real relationship with somebody unless you can tell them to shut up at some point. And we have shut each other up in the most loving ways. One of the great comforts of these last few years was visiting each other without saying, “I’m coming over.” Just being there when somebody needs it — when they don’t expect it and they didn’t ask for it. I love being that way for Dave, and he’s always been that way for me too. So I feel closer to Dave than ever. We’ve done so much stuff together, and really nobody’s helped my career more than Dave Grohl, in terms of just not shutting the hell up about me.

Josh Homme and Dave Grohl at the 56th Grammy Awards in 2014.

(Jason Kempin/WireImage/Getty Images)

Did you learn anything about him over the last 18 months?

Dave is a tough nut to crack, no matter what anyone thinks they know. He keeps that s— in tight. It’s a small group of people that really know Dave. He’s a guy that toughs it out with a smile on his face, and that smile is very disarming to someone else. They go, “Oh, everything’s fine.” I’ve learned that he’d be really good in a foxhole. Not physically — not at all [laughs]. But emotionally.

When’s the last time you cried?

Yesterday. I wanted to call Rio — wanted to call him so bad. Sometimes I just text his phone. I didn’t cry from the time I was 13 until I was deep into my 40s, because that’s the way I was raised. My dad was always like, “This is not the time for you to be sad. We have things we have to do, and then you’ll find your time to deal with that.” And I just never found that time. And then drugs — when you start really doing drugs, you’re just building a callus. And that callus blocks the need to find that time. Eventually, that callus cracks and you almost get drowned in a flood of emotion, which is sort of my last few years. I felt so stupid at the realization of the value of shedding a tear. Physically, there’s holes in your face, and they allow for water to come out. That’s your steam valve. Watching my babies cry when they were infants, I was so intimately involved with the style of their cry. I knew what it meant. But I invested no time at all into the style of my own.

Ever see your dad cry?

I did recently. And I felt happy for him. I have a really tight family: My brother and his husband, who he’s been with since he was 18, and my folks, who are still together, and my three babies — we essentially all live together. Watching my old man cry was like: Yeah, this is overdue for you. Welcome, have a seat. Don’t slip on the water.

Would you have predicted that you’d live as an adult with your parents?

Of course not. I left home four days after my 18th birthday to go on tour. I’ve had an obsession with music that at times has been a possession. I pursued it relentlessly, and I let important things fall apart in that chase. It’s different now. I think the pandemic was great for me because the pandemic asked me, “What do you care about? Pick two things.” And it was my family first and music second. I always thought I had them balanced. But in reality I was chasing music — just out of my mind chasing it so hard.

Josh Homme, in bathtub, and Queens of the Stone Age

(Andreas Neumann)

I think that attitude has led some people to decide there’s something dangerous about you.

I like risky things. I like to throw myself off the cliff. I’m willing to do stuff you aren’t — that’s what separates us.

Does that have a cost?

That image of me as a bad man. But I never minded it because I knew it was partially true. I feel wild sometimes, and I feel a joy from that feral nature. That feels in line with searching for art. But I’d like to think that I understand how to pursue my art without such a reckless abandon.

Do you worry about somebody from your past coming out and saying, “This guy did a bad thing”?

No, because I’ve always had a moral compass. I’ve never been a bully. I’ve got red hair and a gay brother — I’ve always been a bully killer. I want to do the right thing. I realize that my right thing might not always be someone else’s. And I’ve made so many mistakes. Accountability has always been something I’ve lusted after. If I ever ran for office, it would be on the yes-I-did-that ticket.

Let’s finish on a lighter subject. You’ve always carried yourself with a certain amount of style. How much do you think about your physical appearance?

Somewhere between the movie “Real Genius” with Val Kilmer, all of Matt Dillon’s younger life, James Dean, young Elvis Presley and Bill Murray — I’ve been standing in there for my entire life.

Those are your style icons.

Somewhere between “Meatballs” and “Rumble Fish.”

Are you an exerciser?

I’ve become an exerciser.

For health reasons? Vanity reasons? Both?

I’m a shallow bitch. But obviously the health benefits go hand in hand. I’ve had drugged-out, bloated times in my life and was just too deep in that world to give a f—. Now that I’m not in that world, yeah, I’d like to look nice. I try not to sweat it too much.

This story originally Appeared on LATimes